Despite the various types of calamities that have occurred in the last 20 years, the current COVID-19 pandemic seems to have proven once again that supply chains are still not prepared for such disruptions.

There are plenty of examples: SARS in March 2003, the collapse of the banking system in 2008 resulting in the sovereign debt crisis in 2011, the eruption of the Icelandic volcano in March 2010, the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in 2011, or Fukushima in March 2011. These events all revealed the inability of supply chains to react and adapt to unprecedented changes in their ecosystems, resulting in stock interruptions, highly affected service levels, increased Lead Times and the suppression of services, to name a few.

The main effects on supply chains, which are already apparent and will continue to persist, are the following:

- Shortages of raw materials – through the lockdown measures in place or reduction of industrial capacity, globally breaking supply chains;

- Logistic restrictions – transportation of goods, taking into account the limited access to affected areas;

- Scarcity of manpower – reduction in the number of available workers due to quarantine status;

- Changes in consumption – several sectors facing a substantial reduction in demand and changes in consumer habits.

These are not new issues, many of the past crises have had identical shocks to the system. However, the ability to learn from the past has not been best utilised and, in some cases, non-existent.

As COVID-19 spreads globally, there is great uncertainty about the future. However, economic recession and rising unemployment seem inevitable. With all these uncertainties, there is an urgent need to restructure the supply chains to assess and mitigate the risks, acquiring a greater capacity to adapt to the new reality which is precipitously changing. This restructuring requires a deep knowledge of the value chain, something that only a fraction of organisations have.

Companies that invest in the mapping of their value chains are better prepared to address any impact. The information that comes from this extensive mapping allows them to acquire greater knowledge and visibility of the entire value chain, providing teams with a faster and more effective response capability. They understand exactly all levels of suppliers (tier 1, tier 2 and ideally even raw material suppliers), regions in which they operate, components they produce and risk products. Consequently, they can effortlessly identify how their supply chain could be impacted in a period of days, weeks, and months. When companies know in advance where the disruption will occur and which products will be affected, they will need less time to carry out prevention and mitigation strategies. As a result, these companies remain ahead of the curve while the unprepared ones are still collecting and analysing information. In the case of large-scale catastrophes, such as the current pandemic, these value chain maps are used as solution roadmaps to tackle the crisis head-on.

Many companies and leaders feel the need to map their value chains as a risk mitigation strategy. However, these plans hardly materialise, when the amount of time and resource it requires is examined. For a complex value chain, the mapping may take between six months and a year, involving people from different areas of the company and partners (suppliers, 3PL’s, carriers, control towers, among others). Thus, the resources required for the mapping of the supply chain is costly! Consequently, these companies continue to be less prepared without having an agile, flexible value chain that can easily overcome the crises they encounter.

Companies that want to prepare their supply chains for the future must have all of the necessary information and visibility to hand. There is no escape from it, companies will find that the value of mapping is far greater than the cost and time required to develop it.

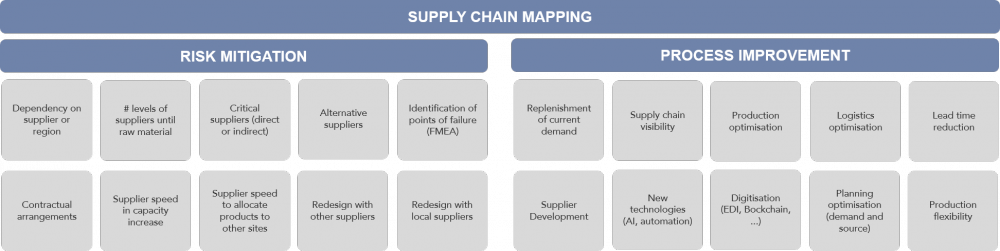

This mapping activity in conjunction with the knowledge held within organisations about their entire value chain makes it possible to highlight all the constraints (heavy, complex structures with high supply Lead Times, among others), which will subsequently trigger a series of improvements to be implemented. Thus, value chain mapping allows us to mitigate risk by focusing on factors such as the degree of dependence on a supplier, identification of critical hidden suppliers, knowledge of alternative supplier sites that could perform the same activity, the time it would take for a supplier to start shipping from an alternative site, etc. Additionally, it allows us to radically improve the speed, agility and flexibility of our value chain, with improvements such as replenishment models based on consumption, reduction of production and logistics Lead Times, increase in speed throughout the chain, increase in capacity and flexibility of production and logistics, and so on.

A supply chain based on consumption – pull – does not reduce inventory by itself. The only impact it has, which is sometimes quite significant, is the suppression of the demand amplification effect – bullwhip. The true stock reduction comes from the increased speed in the supply chain, achieved through high-frequency information and material flows and high flexibility and agility to meet the real demand in all links of the chain. This is achieved by dividing the value chain into small logistics cycles connected through current demand, increasing the frequency of orders and their visibility. Combined with this, the use of tools such as EDI, Blockchain, process digitalisation or quick reference changes, allow an increased frequency of reference repetitions, high availability of equipment (production and logistics) and high stock rotation, which translates into a huge impact on the service level and costs of the entire value chain. Many companies focus on tools or technologies without being clear as to their purpose, applying them incorrectly and therefore not taking full advantage of it.

After the COVID-19 crisis is over, we will see companies falling into one of two categories. The first category will be those that will do nothing, hoping that this interruption will never happen again. This translates into a very risky gamble. In the second category are companies that are looking for longevity and growth, who will use the lessons learned from this crisis, will invest in mapping their value chains to mitigate the risks and avoid operating in the dark when the next crisis occurs. They will also make significant improvements in both the speed and flexibility of their operations. These companies will be the winners in the long term.

#operations #warehousing and transport

See more on Operations

Find out more about transformation in this sector

See more on Warehousing & Transport

Find out more about improving this business area